An Organ Builder Looks Around

A number of more or less extensive travel reports by individual visitors to the Berlin Kunstkammer have survived from the late seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth century. Visitors included such erudite guests as the Dutch philologist Jakob Tollius in 1687, aristocrats on the Grand Tour like the group that accompanied the Austrian Count Rindsmaul 1706, or anonymous travelers from German lands or Italy such as the guest known to scholars as Anonimo Veneziano in 1708. They all saw the notable sights in the Brandenburg-Prussian residential city, toured the princely collections in the library, Antiquities Cabinet, Kunstkammer, and armory, and took notes as recommended by contemporaneous guidebooks on the art of travel. In 1727, Wolff Bernhard von Tschirnhaus published a list entitled “Was merckwürdiges auf der Kunst-Kammer in Berlin zu sehen,” (“Remarkable Things to be Seen at the Kunstkammer in Berlin”) based on his visit on February 27, 1713, presenting it as a Model eines Academie- und Reise-Journals (Model of an Academy and Travel Journal). All these sources are the work of male authors; female voices are perceptible only indirectly.

In 2014, the Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden acquired the travel diary of the Alsatian organ builder Johann Andreas Silbermann (1712–1783). In 1741, the young man from Strasbourg traveled to Central Germany to visit the Saxon homeland of his family of instrument builders. He met its most famous member in Zittau: his uncle Gottfried, whose works number among the highest achievements of Baroque organ art. Johann Andreas would himself produce around five dozen organs in his workshop. Throughout his journey, Silbermann made notes regarding interesting features of the places he visited, complete with sketches, engravings, and newspaper clippings. Hardly surprisingly, he pays the most attention to music and organs; yet during his visit to Berlin, he also devoted sixteen pages to what he saw in the library, Kunstkammer, and Antiquities Cabinet on June 6, 1741 – a Tuesday.

Silbermann’s notes are among a small group of handwritten Kunstkammer reports from around the year 1740, documents that convey a sense of the collection from the perspective of a normal visitor in a period from which virtually no inventories survive. While other guests merely recorded a list of selected objects in a manner very similar to Tschirnhaus’s Model, Silbermann spared no effort to evoke a lively impression of the tour. For example, he was given a fox pelt with two tails “zu visitieren . . . , um zu sehen ob keiner angenähet ist” (“to inspect . . . , in order to see that neither of them was sewn on”), and when “eine vergulde Kugel” (“a gilded ball,” probably from the Pommerschen Kunstschrank) was shaken, “so hörte man darinnen eine sehr schönen und hellen Klang” (“a very lovely and clear sound was audible inside”). Admittedly, Silbermann was writing from memory, since he was not permitted to take notes on his “Schreibtaffel” (“writing tablet”) – a prohibition that was entirely unusual and is mentioned nowhere else, even in Berlin. Had he perhaps annoyed his guide?

Although he was led through the library, Kunstkammer, and Antiquities Cabinet by different officials, neither Silbermann nor other travelers perceived the collections as institutionally separate. He begins his account of the sights by noting, “[S]o viel ich mich noch besinne, so sahe ich zu erst einen Bezoar Bock, welcher aus Africa gekommen” (“as best as I can recall, I saw first a bezoar buck, which came from Africa”), after he had likely entered the Kunstkammer via the spiral staircase from the library, thus bearing witness to the impact of the especially spectacular exhibits presented in the first room of the collection (Room 991/992). Neither the splendid architectural design of the spaces themselves nor the iconography of the ceiling paintings, however, are mentioned in his description.

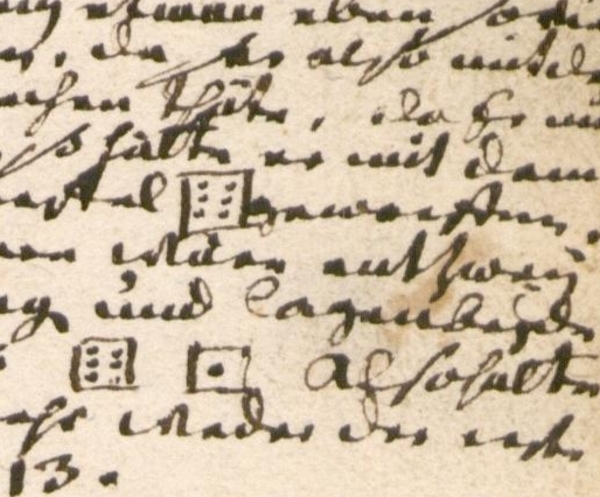

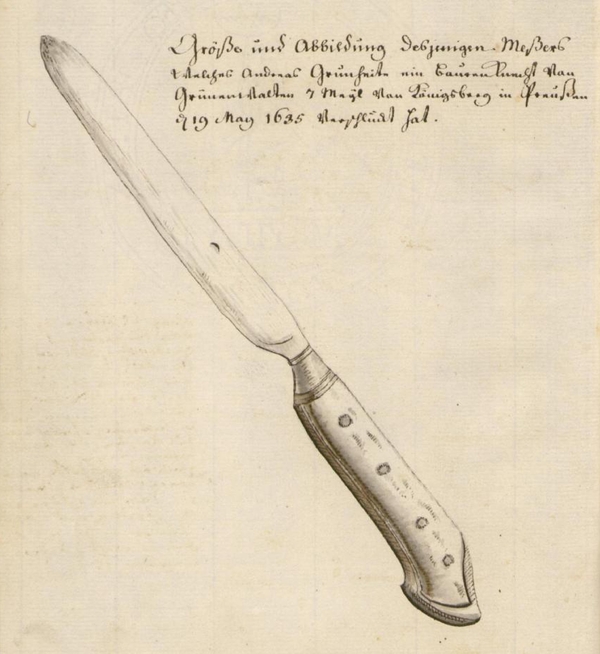

He faithfully recalled the information his guide conveyed to him regarding a selection of objects and in retrospect repeatedly corrected and added to his notes. The “bezoar buck,” Silbermann says, drew its nourishment “von lauter Wurseln” (“from nothing but roots”), and he pays special attention to curiosa such as two cannonballs that had collided in the air at the siege of Magdeburg or the shattered die with which two soldiers played for their lives. For all these objects, he records the anecdotes that were on file in the inventories, stories that were communicated to him orally and from which these often unassuming objects derived their significance in the first place. In the case of a swallowed knife that was surgically removed, he added a drawing – which, unfortunately, does not show the piece in Berlin, but a comparative example.

Works of art were of less interest to him. When he notes with regard to Gottfried Leygebe’s iron statue of the Great Elector, “[d]iese Statue ist unter dreyn die beste gewesen” (“this statue was the best of three”), he is reporting what he had heard, without himself being able to render judgment. Regarding the magnificent goblet of Rudolf II, however—the quintessential Kunstkammer piece – he says: “ich ließ mir denselben zwey mahl weisen, und kunte mich fast nicht satt daran sehen” (“I had it shown to me twice, and I almost couldn’t get enough of seeing it”).

Aside from the “bezoar buck” and two African donkeys [zebras], Silbermann ignored the naturalia in the collection, at least in his recollections. In accord with standard procedure, however, he was instructed to look out the window, prompting him to describe the view of the surrounding terrain as “was unvergleichliches” (“something incomparable”).

Marcus Becker

Objects mentioned by Silbermann in his travel report

For more on this topic, see

Marcus Becker, “A Shattered Die: Playing for Dear Life,” and idem, “Around 1740: Appropriations – The Canon and Visitors’ Journals,” in The Berlin Kunstkammer: Collection History in Object Biographies from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century (Petersberg: Imhof, 2023).